Genetics/Ammonoids

An ammonoid is an extinct cephalopod mollusk with a flat-coiled spiral shell.

An ammonite may be an ammonoid that belongs to the order Ammonitida, typically having elaborately frilled suture lines.

An ammonitic ammonoid in the images on the right shows the septal surface (especially at right) with its undulating lobes and saddles.

Mollusks[edit | edit source]

Def. a "soft-bodied invertebrate[1] [of the phylum Mollusca][2], [typically with a hard shell of one or more pieces]"[3] is called a mollusc.

Def. a "body wall of a mollusc,[4] from which the shell is secreted"[5] is called a mantle.

Def. a "rasping tongue of snails and most other mollusks"[6] is called a radula.

As a mollusk an ammonite may be expected to have

- a mantle with a cavity for breathing and excretion,

- a radula, and

- a structured nervous system.

Cephalopods[edit | edit source]

Def. any "mollusc, [of the class Cephalopoda][7], which includes squid, cuttlefish, octopus, [nautiloids][8] etc"[9] is called a cephalopod.

An ammonite is expected to have cephalopod characteristics

- bilateral body symmetry,

- a prominent head, and

- a set of arms or tentacles (muscular hydrostats).

Theoretical ammonites[edit | edit source]

Def. "the scientific study of squid (often extended to all cephalopods)"[10] is called teuthology.

"Teuthology, a branch of malacology, is the study of cephalopods."[11]

Def. "any of numerous flat spiral fossil shells of cephalopods"[12] is called an ammonite.

We "describe the overall mode of growth of ammonoids with reference to Nautilus, the only externally shelled cephalopod that is still extant. Ammonoids are, in fact, phylogenetically more closely related to coleoids than they are to Nautilus (Engeser, 1990; Jacobs and Landman, 1993; Chapter 1, this volume). However, the retention of an external shell in ammonoids implies that these extinct forms shared with Nautilus basic similarities in their processes of growth, although not necessarily a similarity in their rate of growth or age at maturity."[13]

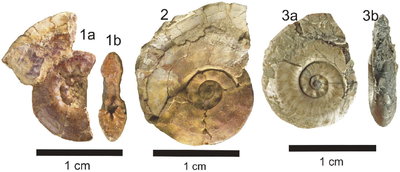

On the right are schematic drawings of four growth stages of Hoploscaphites nicolletii in lateral and transverse cross-sections:

- A is an embryonic shell called the ammonitella, scale bar 500 µm,

- B is the first postembryonic stage called the neanic and the animal or shell is called the neanoconch, scale bar 1 mm,

- C is a juvenile, scale bar 5 mm, and

- D is an adult, scale bar is 1 cm.[13]

Agoniatites[edit | edit source]

Agoniatites are also known as Anarcestes.

Agoniatites vanuxemi, on the lower right, is the only species of Ammonoid found in the Hamilton Group, Mahantango Formation.

Ammonites[edit | edit source]

These are ammonites of the suborder Ammonitida.

Ceratites[edit | edit source]

A ceratite may be an ammonoid of an intermediate type, typically with partly frilled and partly lobed suture lines.

"The Ceratitida, which is the dominant ammonoid order of the early Mesozoic and one of the major orders of Ammonoidea, ranged from early Permian to the end of Triassic times, and has an almost worldwide distribution (Hewitt et al., 1993; Page, 1996)."[14]

Clymeniids[edit | edit source]

Any clymeniid may be an ammonoid with a dorsal siphuncle; i.e., a siphuncle on the inside of the coil rather than the outside.

Goniatites[edit | edit source]

An ammonoid like the one on the right typically with simple angular suture lines is referred to as a goniatite.

Lytocerates[edit | edit source]

Characteristics:

- loosely coiled,

- evolute,

- gyroconic,

- exposed whorls,

- whorls touching,

- subcircular to narrowly compressed whorls,

- broadly arched, or keeled venter,

- smooth or ribbed sides,

- aptychi are single valved and concentrically striated,

- suture saddle endings tend to be rounded but usually not phylloid,

- lobes tend to be more jagged with thorn-like endings, and

- complex moss-like suture endings with adventious and secondary subdivisions.

Nostoceratids[edit | edit source]

Nipponites mirabilis on the right may be from the Upper Cretaceous.

Phyllocerates[edit | edit source]

Prolecanites[edit | edit source]

"Type species by original designation of Librovitch 1957, Protocanites supradevonicus Schindewolf (1926)."[15]

In the diagrams above are the suture patterns for various species holotypes:

- A - Protocanites gurleyi (Smith),

- B - Eocanites supradevonicus supradevonicus (Schindewolf),

- C - Eocanites semageominus (House),

- D - Eocanites wangyounensis(Ruan & He),

- E - Michiganites algarbiensis (Pruvost),

- F - Michiganites marshallensis (Winchell),

- G - Michiganites scalibrinii (Antelo),

- H - Michiganites greenei (Miller).[15]

Coleoids[edit | edit source]

The subclass Coleoidea has the cohort Belemnoidea which may contain shelled cephalopods.

Neocoleoids[edit | edit source]

The image on the right shows "the piglet squid [Helicocranchia pfefferi], floating along with its tentacles waving above its head in the central Pacific Ocean near Palmyra Atoll."[16]

The "squid [was spotted] about 4,544 feet (1,385 meters) below the ocean surface [from] the exploration vehicle (E/V) Nautilus."[16]

"Is that a squid? I think it's a squid. It's like a bloated squid with tiny tentacles and a little hat that's waving around. And it looks like it's got a massive, inflated mantle cavity. I've never seen anything quite like this before."[17]

The "mantle is filled with ammonia, which the squid uses to control its buoyancy."[16]

"This Nautilus expedition is an effort to explore the deep ocean waters of the Marine National Monument, near Kingman Reef, Palmyra Atoll and Jarvis Island, which are among the most remote U.S.-controlled territories."[16]

Helicocranchia is of the order Teuthida.

Belemnoids[edit | edit source]

The cohort Belemnoidea has five extinct orders. Any one of these may contain cephalopods with an external shell.

"Belemnites (Belemnitida) were squid-like animals belonging to the cephalopod class of the mollusc phylum, and therefore related to the ammonites of old as well as to the modern squids, octopuses and nautiluses."[18]

"Now extinct, their fossils are found in rocks of Jurassic and Cretaceous ages, with a few species hanging on into the early part of the Tertiary. The animal’s soft parts very rarely fossilise, leaving us with only the hard parts; the guard and the phragmacone."[18]

Aulacocerids[edit | edit source]

"Pendleian age rocks in the Chainman Shale include the upper beds of the Camp Canyon Member and the Willow Gap Limestone Member. The fossil cephalopods [an example of Hematites barbarae is shown above] are from these rocks in the Confusion Range and Burbank Hills of western Millard County."[19]

For the study of the "shell morphology and ultrastructure in Hematites [more] than 30 specimens of this genus were collected by the second author from the Upper Mississippian in Arkansas. The data obtained confirm the detailed description of the external shell morphology [diagrammed on the right] in the genus published by FLOWER & GORDON (1959) and GORDON (1964), and it also includes new information on the conotheca structure, conotheca rostrum/mantle attachment, “living” chamber length, and morphology of the adoral portion of the rostrum."[20]

"Schematic diagram of the medial shell section in Hematites [on the right shows] the truncation of the initial portion of the phragmocone which is plugged by the central rod structure (crs) and by the additional septum (as). Scale bar: 1 mm. as = additional septum; c = conotheca; r = rostrum; s = septum; sn = septal neck; t = place of truncation."[20]

Phragmoteuthids[edit | edit source]

The image on the right suggests that Phragmoteuthis conocauda does not have an external shell.

Belemnitids[edit | edit source]

"Belemnites [...] have a worldwide distribution."[21]

Shells or shell-like structures are the phragmacone in the image on the left and the rostrum, the second image on the left, which have been found apparently internal to the soft body. The second image down on the left shows rostrums from Passatoteuthis auricipitis Lang, Jurassic, Lower Lias, found in Gloucestershire.

The image second down on the right shows a rostrum from the genus Peratobelus, found in the Cairn mine, South Australia.

Diplobelids[edit | edit source]

Belemnoteuthins[edit | edit source]

Nautiloids[edit | edit source]

Def. a cephalopod mollusk with a light external spiral shell that is white with brownish bands on the outside and lined with mother-of-pearl on the inside is called a nautiloid.

Nautiloidea is another subclass of cephalopods.

"Nautilus [included in the diagram on the left] is one of the few surviving animals resembling the primitive or original cephalopods. The fossilized shells of these extinct forms, called ammonites (A), are quite common. (B) is a deep-sea species Nautilus pompilius that lives in tropical waters. To the right is a section through Nautilus showing the shell (1) and siphuncle (2) wound in a spiral. Immediately behind the tentacles lies the mouth (4) leading to the intestine (7). Nautilus has an advanced nervous system with a brain (3) and respires by means of gills (6) that are located in the mantle cavity. It swims by forcing a jet of water out of its mantle cavity and through the siphon (5)."[22]

"Nautiluses first evolved in the Cambrian period and became significant marine predators during the Ordovician period."[22]

Actinocerids[edit | edit source]

Ascocerids[edit | edit source]

Bactrites[edit | edit source]

Barrandeocerids[edit | edit source]

Discosorids[edit | edit source]

Ellesmerocerids[edit | edit source]

Endocerids[edit | edit source]

Nautilids[edit | edit source]

An individual example of the genus Nautilus is on the right.

A couple of Nautilus macromphalus are on the left, photographed during a night dive, at 15 meters, near Lifou, Sandal wood bay, New Caledonia.

"The six living species of nautiluses are:

- No common name (Allonautilus perforates),

- Crusty Nautilus (Allonautilus scrobiculatus),

- Palau Nautilus (Nautilus belauensis),

- Bellybutton Nautilus (Nautilus macromphalus),

- Chambered Nautilus (Nautilus pompilius), and

- White-patch Nautilus (Nautilus stenomphalus)".[22]

Oncocerids[edit | edit source]

Orthocerids[edit | edit source]

Centered at the top is an artist's impression of an Orthoceras species from the middle Ordovician.

On the left is a fossil of Orthoceras currens.

Plectronocerids[edit | edit source]

Pseudorthocerids[edit | edit source]

Tarphycerids[edit | edit source]

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Cut in the plane of the spiral (medial or median cut), the shell reveals the chambers inside.

On the left is an internal mold from a Baculites individual. The original aragonite of the outer conch and inner septa has dissolved away, leaving this articulated internal mold. Baculites is an ammonite from the Late Cretaceous of Wyoming.

The tissue used to close the chamber to the outside is called an aptychus. Perisphictes on the lower left has aptychi.

Agoniatites have a central siphuncle as shown in the illustration on the right with septal necks pointing to the rear (retrochoanitic).

The diagrams on the lower left show median sections where the siphuncle is in a ventral position. Measurements to characterize an ammonite are indicated in the right-hand diagram. The abbreviations are for ammonitella (am), caecum (c), initial chamber (ic), primary constriction (pc), prosiphon (ps), siphunclar tube (s), proseptum (first septum, s1), primary septum (second septum, s2), third septum (s3), maximum initial chamber size (A), minimum initial chamber size (B), ammonitella size (D), and ammonitella angle (E).[14]

Predation[edit | edit source]

The fossil shell of ammonite Placenticeras whitfieldi on the right shows punctures caused by the bite of a mosasaur.

"In the late Cretaceous, it is the mosasaurs that have been identified as ammonite predators, beginning with the study of Kauffman and Kesling (1960), who described a 300 mm diameter Placenticeras (first illustrated by Fenton and Fenton in 1958) from the Late Campanian Pierre Shale of South Dakota that had been bitten, in their interpretation no less than 16 times, by what they concluded to be a platycarpine mosasaur (we suggest that the mosasaur was playing with its prey, as do contemporary cetaceans)."[23]

"A juvenile specimen of the ammonite Pseudaspidoceras [in the image on the left] from the Early Turonian [Late Cretaceous] of the Goulmima area in the Province of Er-Rachida in south-eastern Morocco shows clear evidence of predation by a tooth-bearing vertebrate."[23]

"These [teeth punctures] are interpreted as the product of a single bite by a mosasauroid, probably a Tethysaurus."

"All of the convincing well-documented examples of mosasaur-bitten ammonite shells are thus from North America, the overwhelming majority from the Late Campanian of the northern part of the Western Interior of the United States and Alberta in Canada."[23]

"The Goulmima occurrence is the only convincing record of mosasauroid attack on an ammonite outside North America, and of the latter, the overwhelming majority are restricted to the Late Campanian of the northern interior. The only adequately documented putative occurrence outside of the interior, in the Early Maastrichtian Rosario Formation of Baja California, Mexico, may not in fact be by a mosasaur, although there is evidence of mosasauroid attack on two Campanian nautiloids from San Diego County in California."[23]

"Given the above, we see no evidence to support the view that there was coevolution between ammonites and mosasaurs, nor that mosasaurs were "The ecologically dominant predators of Cretaceous marine seas" as proposed by Kauffman (1990)."[23]

Sizes[edit | edit source]

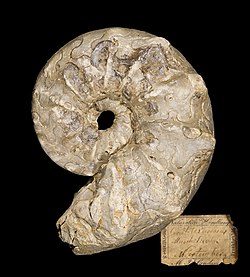

On the right is an image of the world's largest known ammonite, Parapuzosia seppenradensis (originally Pachydiscus seppenradensis) discovered in Seppenrade, Germany. The partial fossil specimen has a shell diameter of 1.95 metres (6.4 ft). But, the living chamber was incomplete. The shell diameter may have been about 2.55 metres (8.4 ft) when it was alive.

Cenozoic[edit | edit source]

Paleocene[edit | edit source]

The Paleocene dates from 65.5 ± 0.3 x 106 to 55.8 ± 0.2 x 106 b2k.

Danian[edit | edit source]

The beginning of the Danian age (and the end of the preceding Maastrichtian age) is at the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event at 66.0 Ma. The age ended 61.6 Ma, being followed by the Selandian age.[24]

Post-"Cretaceous ammonites of the genus Hoploscaphites have been found at Stevns Klint in Denmark (Machalski & Heinberg, 2005; Machalski et al., 2009)."[25]

"The maximum age for Danian scaphitid survivors from the Cerithium Limestone at Stevns Klint, Denmark, has recently been estimated to be around 0.2 Ma following the K–Pg boundary event (Machalski and Heinberg in press). Assuming the Cretaceous– Paleogene boundary at 65.4 ± 0.1 Ma (Jagt and Kennedy 1994), the present study covers more than 4 Ma of the final stages in scaphitid evolution."[26]

"Scaphitid material from subunit IVf−7 at the very top of the Meerssen Member [...] traditionally regarded to be uppermost Maastrichtian, has recently been reassigned to the lowermost Danian, based on microfossil and strontium isotope evidence (Smit and Brinkhuis 1996). According to Jagt et al. (2003), the scaphitid and baculitid ammonites preserved in subunit IVf−7 are early Danian survivors."[26]

Above center are Hoploscaphites constrictus johnjagti subsp. nov., adult macroconchs, ammonites from the Danian: A. MGUH 27366, lowermost Danian, Stevns Klint, Denmark, in apertural (A1), lateral (A2, A3), and ventral (A4) views.

Mesozoic[edit | edit source]

The Cretaceous/Cenozoic boundary occurs at 65.0 ± 0.1 Ma (million years ago).[27]

Cretaceous[edit | edit source]

"The Cretaceous period is the third and final period in the Mesozoic Era. It began 145.5 million years ago after the Jurassic Period and ended 65.5 million years ago, before the Paleogene Period of the Cenozoic Era."[28]

Scaphites hippocrepis is an index fossil for the Cretaceous.[29]

Late Cretaceous[edit | edit source]

In the top center is a 2.7 cm section of a polished shell with 6 sutures. It is from the extinct cephalopod Baculites compressus; Cretaceous, 100 million years old, Bearpaw Formation, Montana, USA.

The lower center is a fossil cast of a Baculites grandis shell taken at the North American Museum of Ancient Life.

On the right is an example of Plesiacanthoceras wyomingense from the late Cretaceous in Wyoming, USA. It is exhibited in Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History: Hall of Fossils.

Lancian[edit | edit source]

The Lancian ranges from 66.8 to 65.5 Ma (K/T boundary).

Maastrichtian[edit | edit source]

Extends from 70.6 ± 0.6 to 65.5 ± 0.3 Mya.

The specimen on the left is Jeletzkytes spedeni from the Maastrichtian (Upper-Cretaceous) Fox Hills Formation, locality - South Dakota, USA. Matrix free specimen is 7.5 cm (3") in diameter, displaying pearly aragonite preservation of the shell.

The center photo is of Baculites ovatus, at the Naturalis Museum, Leiden.

Baculites ovatus apparently occurs in the Ripley Formation.[30]

Discoscaphites iris on the right is an ammonite from the Owl Creek Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Owl Creek, Ripley, Mississippi USA.

The McNairy Formation found in Illinois is also from the Upper Cretaceous Maastrichtian.

Baculites baculus, type specimen in the image at lower right, lower boundary of zone and lower boundary for Maastrichtian dated to 70.6 ± 0.6 Ma and upper boundary dated to 70.00 ± 0.45 Ma.[31]

Kirtlandian[edit | edit source]

The Kirtlandian ranges from 75.6 to 72.8 Ma.

Edmontonian[edit | edit source]

Edmontonian extends from 80.8 to 70.7 Mya.

The fossil shown on the right has a bizarre and irregularly shaped shell. Such examples are called heteromorph ammonites.

Classification: Animalia, Mollusca, Cephalopoda, Ammonoidea, Ancyloceratina, Nostoceratidae.

"The Williams Fork Formation represents a period spanning seven ammonite zones from the Didymoceras cheyennense to the Baculites baculus (Meek and Hayden, 1861) Zone (Newman, 1987). Based on the timescale of Obradovich and Cobban (1975), these seven ammonite zones represent approximately three million years, correlative with the late Campanian to early Maastrichtian (Harland et al., 1990). Lillegraven and Ostresh (1990) correlated these seven ammonite zones to the Edmontonian North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA)."[32]

Other ammonite zones include Baculites compressus from the Fruitland Formation above the Didymoceras cheyennense zone.[33] "Baculites compressus age is from a bentonite bed in the Bearpaw Shale, Big Horn County, Montana (Obradovich, 1993 and written communication, Obradovich, 1996)."[33]

The stratigraphic column on the left shows ammonite zones between Didymoceras nebrascense and the Maastrichtian with inferred ages.

Bentonite "marker beds are found throughout the lowermost Williams Fork Formation and the underlying Cameo Coal interval [...] the Yampa ash marker bed, is found near the top of the Cameo Coal interval, suggesting a depositional age equal to or younger than 72.2 ± 0.1 Ma for the lower Williams Fork Formation [...] and time equivalent to the previously mentioned Baculites reesidei zone (Brownfield and Johnson 2008) [...]."[34]

Judithian[edit | edit source]

Extends from 82.2 to 80.8 Mya.

Campanian[edit | edit source]

The Bearpaw Formation is famous for its well-preserved ammonite fossils. These include Placenticeras meeki and Placenticeras intercalare, and the baculite Baculites compressus.[35]

Extends from 83.5 ± 0.7 to 70.6 ± 0.6 Mya.

The Baylis Formation, Post Creek Formation and the Tuscaloosa Formation are Upper Cretaceous from the Campanian.

Haumurian[edit | edit source]

Extends from 84 to 65.5 Mya.

Aquilan[edit | edit source]

Extends from 85.2 to 82.2 Mya.

Santonian[edit | edit source]

Extends from 85.8 ± 0.7 to 83.5 ± 0.7 Mya.

Piripauan[edit | edit source]

Extends from 86.5 to 84 Mya.

Teratan[edit | edit source]

Extends from 89.1 to 86.5 Mya.

Coniacian[edit | edit source]

Extends from 89.3 ± 1.0 to 85.8 ± 0.7 Mya.

Senonian[edit | edit source]

Extends from 89.3 to 65.5 Mya.

Emscherian[edit | edit source]

Extends from 89.5 to 83.5 Mya.

Mangaotanean[edit | edit source]

Extends from 92.1 to 89.1 Mya.

Turonian[edit | edit source]

Extends from 93.5 ± 0.8 to 89.3 ± 1.0 Mya.

Benueites is a Turonian ammonite genera from Nigeria.[36]

Cenomanian[edit | edit source]

These fast-moving nektonic carnivores lived during the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous (from 94.3 to 89.3 Ma).[37][38]

Middle Cenomanian[edit | edit source]

The hierarchy of ammonites in the Middle Cenomanian is shown on the left below beginning at 95.73 ± 0.61.[39]

| Subdivisions of the Middle Cenomanian | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Western Interior Ammonite Taxon Range Zones |

Age Ma | Species image |

| Middle Cenomanian |

Plesiacanthoceras wyomingense |

>94.71 ± 0.49 |  |

| Acanthoceras amphibolum |

<94.96 ± 0.50 |  | |

| Acanthoceras bellense |

<95.73 ± 0.61 |  | |

| Acanthoceras muldoonense |

<95.73 ± 0.61 |  | |

| Acanthoceras granerosense |

<95.73 ± 0.61 |  | |

| Conlinoceras tarrantense |

<95.73 ± 0.61 |  | |

Shells of Acanthoceras rhotomagensis may reach a diameter of about 36–50 centimetres (14–20 in). Their shells have ornate ribs.[40][41]

Acanthoceras rhotomagensis fossils may be found in Western Europe and western North America.[42]

Acanthoceras rhotomagensis fossils occur in the Middle Cenomanian just above the boundary with the Lower Cenomanian.[23]

The "highly fossiliferous marl, 1 m in thickness, is the Cast Bed of Price (1877), [where the] lowest record of Acanthoceras rhotomagensis (Brongniart)" occurs.[23]

Lower Cenomanian[edit | edit source]

Hibolites is a genus of belemnite, an extinct group of cephalopods of the Lower Cenomanian.[43]

The Lower Cenomanian extends from 99.6 ± 0.9 Ma to 95.73 ± 0.61 Ma.[44]

Arowhanan[edit | edit source]

Extends from 95.2 to 92.1 Mya.

Lower Cretaceous[edit | edit source]

Albian[edit | edit source]

Puzosia is a genus of Desmoceratidae (desmoceratid) ammonites, and the type genus for the Puzosiinae, which lived during the middle part of the Cretaceous, from early Aptian to Maastrichtian (125.5 to 70.6 Ma).[45] Or, the range is from Albian to Santonian.[46]

Otohoplites is a genus of ammonite that lived in the Early Albian whose fossils were found in Svalbard, Denmark, England, France, Austria, Poland, Russia and Kazakhstan, evolved from Hemisonneratia and gave rise to genus Hoplites.[47] Shells belonging to this genera are rather inflated to compressed and have zigzaging, or looped ribs that ends in oblique ventrolateral clavi; usually, ribs are zigzaging through venter; macroconchs have smooth body chamber and rounded venter.[48]

Kossmatella is an extinct genus of ammonoid cephalopods belonging to the family Lytoceratidae, were fast-moving nektonic carnivores[49] that lived from Albian to Cenomanian age.[46]

Cleoniceras included in the subfamily Cleoniceratinae is a rather involute, high-whorled hoplitid from the Lower to basal Middle Albian of Europe, Madagascar, and Transcaspian region, where the shell has a generally small umbilicus, arched to acute venter, and typically at some growth stage, falcoid ribs that spring in pairs from umbilical tubercles, usually disappearing on the outer whorls.[50]

Brancoceras is a rather small, strongly ribbed, acanthoceratacean ammonite from the Albian stage of the Lower Cretaceous:[51][52]

- the shell is evolute with a subquadrate whorl section and rounded venter

- the suture forms a finely squiggly line with well-defined lobes and saddles

- Brancoceras (Eubrancoceras) aegoceratoides reached a diameter of at least 4.2 centimetres (1.7 in)

- Brancoceras is representative of the subfamily Brancoceratinae, which makes up part of the Acanthoceratoidea (acanthoceratacean) family Brancoceratidae

- stratigraphic range is rather narrow, extending only from the upper Lower to the Middle Albian.

Arcthoplites is an extinct genus of cephalopod belonging to the Ammonite subclass from the lower Albian.[46]

Anadesmoceras is an hoplitid ammonite from the lower Albian (upper Lower Cretaceous) of England, included in the subfamily Cleoniceratinae:

- a shell shaped more or less like a compressed Cleoniceras but with faint ornament only on the inner whorls

- the shell has bundled growth striae. The aperture is preceded by several wide sinuous constrictions.[46][51]

Anacleoniceras is an extinct genus of cephalopod belonging to the Ammonite subclass lower Albian.[46]

Aioloceras is an ammonite, order Ammonitida, from near the end of the Early Cretaceous:[46][51]

- the shell is compressed with the outer whorl covering much of the previous

- sides are slightly convex, converge toward a narrowly ached venter

- inner whorls have sharp falcoid ribs, outer are smooth

- umbilical tubercles are lacking

- similar related forms include Neosaynella and Cleoniceras

- has been found in Albian (uL Cret) sediments in Madagascar, Patagonia, and possibly Queensland.

Lower Albian[edit | edit source]

"Amber—ancient resins from trees—commonly traps only some terrestrial insects, plants, or animals. It’s very rare to find some sea animals in amber."[53]

"This extraordinary assemblage, a true and beautiful snapshot of a beach in the Cretaceous, is just mind-blowing."[54]

"The idea that there’s a whole community of organisms in association—that may prove more important in the long run."[55]

"If you were scuba-diving in a shallow marine setting, you absolutely would have seen ammonites. They would be as common as seeing some snails crawling around."[56]

"Based on its internal shell structure, the amber-encased ammonite is a juvenile that belongs to the subgenus Puzosia (Bhimaites), which makes a lot of sense in 99-million-year-old amber."[53]

Aptian[edit | edit source]

Barremian[edit | edit source]

Hauterivian[edit | edit source]

Valanginian[edit | edit source]

Berriasian[edit | edit source]

Early Cretaceous[edit | edit source]

Jurassic[edit | edit source]

The Jurassic/Cretaceous boundary occurs at 144.2 ± 2.6 Ma (million years ago).[27]

Perisphinctes tiziani is an index fossil for the Jurassic.[29]

Late Jurassic[edit | edit source]

On the right is an example of Kosmoceras cromptoni from the Late Jurassic, Chippenham, England.

Upper Jurassic[edit | edit source]

Tithonian[edit | edit source]

Kimmeridgian[edit | edit source]

Lithacosphinctes achilles is from the Kimmeridgian.

Oxfordian[edit | edit source]

Middle Jurassic[edit | edit source]

Callovian[edit | edit source]

On the right is an image of Peltoceras solidum, an ammonite from the Matmor Formation (Jurassic, Callovian), Makhtesh Gadol, Israel.

On the left is an example of Kosmoceras medea.

Another species of Kosmoceras is on the lower right, specifically Kosmoceras proniae.

Bathonian[edit | edit source]

Bajocian[edit | edit source]

Aalenian[edit | edit source]

Leioceras opalinum is an ammonite from the Aalenian.

Lower Jurassic[edit | edit source]

Uptonia jamesoni from the lower Jurassic is in the family Polymorphitidae, superfamily Eoderocerataceae, order Ammonitida, subclass Ammonoidea, class Cephalopoda.

Toarcian[edit | edit source]

Pliensbachian[edit | edit source]

Pleuroceras spinatum (Bruguière 1789) is of the family Amaltheidae. It is a pyritic specimen. The biozone index is to the end of Pliensbachian.

The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) has assigned the First Appearance Datum of Bifericeras donovani and of genus Apoderoceras the defining biological marker for the start of the Pliensbachian Stage of the Jurassic, 190.8 ± 1.0 million years ago.[57]

Sinemurian[edit | edit source]

"During the Lower Lias, deposition of lower and middle formations (Hettangian-Sinemurian) occurs under a low bathymetry."[58]

On the left is a photograph of Asteroceras obtusum from the Jurassic Lower Lias Formation, Obtusum Zone. Locality is Lyme Regis, Dorset, England. Complete calcified specimen measures 11.5 cm (4.5") in diameter, in a limestone matrix.

Hettangian[edit | edit source]

Psiloceras psilonotum, Psiloceras spelae tirolicum and Psiloceras planorbis are from the Hettangian.

The Triassic/Jurassic boundary occurs at 205.7 ± 4.0 Ma (million years ago).[27]

Triassic[edit | edit source]

Although the example of Psiloceras tilmanni is from the Jurassic. Its lowest occurrence is in the New York Canyon section of Nevada USA which may be Triassic.

Trophites subbuliatus is an index fossil for the Triassic.[29]

Upper Triassic[edit | edit source]

Rhaetian[edit | edit source]

Norian[edit | edit source]

Carnian[edit | edit source]

Middle Triassic[edit | edit source]

Ladinian[edit | edit source]

Anisian[edit | edit source]

An example of Ussuriphyllites amurensis (Kiparisova) is on the right. It is from the Lower-most Anisian, Atlasov Cape area.[59]

Lower Triassic[edit | edit source]

Olenekian[edit | edit source]

Spathian[edit | edit source]

The Spathian is sometimes referred to as the Late Olenekian.[60]

Olenekoceras meridianum is a "typical Late Olenekian [fossil which] differs in its lithology from the same zone of Russian Island, where the Zhitkov Suite has been recognized (Zakharov, 1997; Zakharov et al., 2004)."[59]

Smithian[edit | edit source]

The Smithian is sometimes referred to as the Early Olenekian.[60]

Induan[edit | edit source]

Paleozoic[edit | edit source]

The Paleozoic era spanned 542.0 ± 1.0 to 251.0 ± 0.7 Mb2k.

Permian[edit | edit source]

The Permian lasted from 299.0 ± 0.8 to 251.0 ± 0.4 Mb2k.

The Permian/Triassic boundary occurs at 248.2 ± 4.8 Ma (million years ago).[27]

Carboniferous[edit | edit source]

The Carboniferous began 359.2 ± 2.5 Mb2k and ended 299.0 ± 0.8 Mb2k.

Pennsylvanian[edit | edit source]

The Pennsylvanian lasted from 318.1 ± 1.3 to 299.0 ± 0.8 Mb2k.

Reticuloceratidae, subtaxa: Aphantites, Gaitherites, Marianoceras, Melvilloceras, Surenites, Ugamites, Verneuilites, age range: 318.1 to 314.6 Ma, Distribution: Carboniferous of Canada (2: Nunavut collections), the Russian Federation (13), United States (25: Arkansas), Uzbekistan (3).[61][62]

Lower Pennsylvanian[edit | edit source]

Aphantites aenigmaticus ranges from 314.2 Ma to 313 Ma.[63]

Mississippian[edit | edit source]

The Mississippian lasted from 359.2 ± 2.5 to 318.1 ± 1.3 Mb2k.

Prolecanites gurleyi is an index fossil of the Mississippian.[29]

Middle Mississippian[edit | edit source]

"This species has been consistently identified with the considerably younger, late Viséan (late Holkerian to Asbian [late Meramecian to early Chesterian]) genus Beyrichoceras Foord, 1903 (type species, Goniatites obtusus Phillips, 1836) (eg, Gordon, 1965, p. 284."[64]

Devonian[edit | edit source]

The Devonian spanned 416.0 ± 2.8 to 359.2 ± 2.5 Mb2k.

Upper Devonian[edit | edit source]

Famennian[edit | edit source]

A specimen of Clymenia laevigata from the Upper Devonian Famennian of Poland is on the right.

On the left is a fossil of Platyclymenia intracrostata also from the Famennian of Poland.

Frasnian[edit | edit source]

Middle Devonian[edit | edit source]

Givetian[edit | edit source]

Eifelian[edit | edit source]

Lower Devonian[edit | edit source]

Emsian[edit | edit source]

Pragian[edit | edit source]

Lochkovian[edit | edit source]

Early Devonian[edit | edit source]

Mimagoniatites is a genus of ammonites from the early Devonian.

"Shell [is] small to large size, evolute, thinly discoidal to discoidal. Whorl cross section of the first two whorls [is] approximately circular, in later whorls subtrapezoidal. Umbilicus [is] narrow to moderately wide, moderately large umbilical window (< 1 mm). Whorl expansion rate increases remarkably from the second whorl on (> 2.5, later up to 3.9). Growth line course [is] biconvex with prominent ventrolateral projection and deep ventral sinus."[65]

The lower boundary of the genus is "LD3C--LD3D: Anetoceras Range Zone top, 405.5 million years" and the upper boundary is "CZB maureri--sulc.antiqua Zone [19,30], 398.5 million years".[65]

Geographic distribution: "Devonian of Algeria (2 collections), Canada (1: Nunavut), China (7), the Czech Republic (5), Germany (3), Morocco (13), the Russian Federation (1), Spain (4), Turkey (3), United States (1: Pennsylvania)".[66]

Silurian[edit | edit source]

The Silurian spanned 443.7 ± 1.5 to 416.0 ± 2.8 Mb2k.

Hexamoceras hertzeri is an index fossil for the Silurian.[29]

Hexamoceras is a genus of the Nautiloidea.[67]

"Rolfe made the important observation that 'Other genera are pre-Devonian and hence cannot be ammonoid aptychi, but Ruedemann's suggestion that aptychi "would naturally also have existed in the Ordovician and Silurian cephalopods" has been largely overlooked'."[68]

Ordovician[edit | edit source]

The Ordovician lasted from 488.3 ± 1.7 to 443.7 ± 1.5 Mb2k.

The Nautiloidea fossil Discoceras boreale has been found in Middle and Upper Ordovician sediments in Northern Europe, Baffin Island in Canada, Yunnan and Hubei provinces in China, and in Punjab, India.

Upper Ordovician[edit | edit source]

The image on the right is an over-encrusted, internal mold of a nautiloid from the Upper Ordovician of northern Kentucky.

Cambrian[edit | edit source]

The Cambrian lasted from 542.0 ± 1.0 to 488.3 ± 1.7 Mb2k.

Middle Cambrian[edit | edit source]

"The fossils date to the early Cambrian period and are about 522 million years old, according to the researchers, who found the fossils on the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland, Canada. Until now, the oldest cephalopod on record was a shelled creature known as Plectronoceras cambria, which lived about 30 million years after the recently discovered, yet-to-be-named cephalopod."[69]

The finding suggests "that cephalopods emerged at the very beginning of the evolution of multicellular organisms during the Cambrian explosion."[70]

"The fossils show that this ancient creature had a cone-shape shell that was subdivided into different chambers. These chambers were connected by a siphuncle — an internal tube seen in shelled cephalopods, including extinct ammonites and modern-day nautiluses — that pumps fluids and gases through the different chambers to help the animal adjust its buoyancy."[69]

"By evolving a siphuncle, cephalopods became the first known organisms to be able to actively move up and down in the water. With this ability to move, early cephalopods picked the open ocean as their chosen habitat."[70]

"The fossils were discovered on the ancient micro-continent of Avalonia, which encompassed parts of eastern Newfoundland and Europe."[70]

"Although an early Cambrian origin of cephalopods has been suggested by molecular studies, no unequivocal fossil evidence has yet been presented. Septate shells collected from shallow-marine limestone of the lower Cambrian (upper Terreneuvian, c. 522 Ma) Bonavista Formation of southeastern Newfoundland, Canada, are here interpreted as straight, elongate conical cephalopod phragmocones. The material documented here may push the origin of cephalopods back in time by about 30 Ma to an unexpected early stage of the Cambrian biotic radiation of metazoans, i.e. before the first occurrence of euarthropods."[71]

"We recently redescribed the Middle Cambrian organism Nectocaris pteryx known from 92 specimens from the Burgess Shale (Smith & Caron 2010). [This] new material allowed us to identify new features consistent with a cephalopod affinity."[72]

Hypotheses[edit | edit source]

Hypotheses:

- Each of the ammonoids has a set of genes producing a distinct suture mark.

- Ammonoids are alive today.

- Morphological descriptions should be sufficient to identify unknown ammonites at the species level.

Sciences[edit | edit source]

Classification of Baculites ovatus:

- Domain: Eukaryota

- Regnum: Animalia

- Subregnum: Eumetazoa

- Cladus: Bilateria

- Superphylum: Protostomia

- Phylum: Mollusca

- Classis: Cephalopoda

- Subclassis: Ammonoidea

- Ordo: Ammonitida

- Subordo: Ancyloceratina

- Superfamilia: Turrilitoidea

- Familia: Baculitidae

- Genus: Baculites

- Species: Baculites ovatus (Say, 1820)

The subclassis: Ammonoidea contains the ordines: Ammonitida, Ceratitida, Clymeniida, Goniatitida, and Prolecanitida.

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Piolinfax (11 November 2003). "mollusc". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ EncycloPetey (6 March 2006). "mollusc". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ Pathoschild (30 December 2006). "mollusc". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ SemperBlotto (18 October 2005). "mantle". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ EncycloPetey (2 August 2010). mantle. San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/mantle. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

- ↑ EncycloPetey (7 September 2008). "radula". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

- ↑ SemperBlotto (1 February 2007). "cephalopod". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ Hekaheka (17 April 2008). "cephalopod". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ Trunkie (31 August 2004). "cephalopod". San Francisco, California: Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ William C. Summers (1990). Daniel L. Gilbert, William J. Adelman Jr. and John M. Arnold. ed. Natural History and Collection, Chapter 2, In: Squid as Experimental Animals. Springer. pp. 11-25. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-2489-6_2. ISBN 978-1-4899-2491-9. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4899-2489-6_2. Retrieved 2015-01-31.

- ↑ L. Zawilinski; A. Carter; I. O'Byrne; G. McVerry; T. Nierlich; D. Leu (2007). Towards A Taxonomy Of Online Reading Comprehension Strategies. University of Connecticut. http://webdev.education.uconn.edu/static/sites/newliteracies/iesproject/documents/NRCStrategiesPaper.doc. Retrieved 2015-01-31.

- ↑ Philip B. Gove, ed (1963). Webster's Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary. Springfield, Massachusetts: G. & C. Merriam Company. pp. 1221.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hugo Bucher; Neil H. Landman; Susan M. Klofak; Jean Guex (1996). Neil H. Landman, Kazushige Tanabe, and Richard Arnold Davis. ed. Mode and Rate of Growth in Ammonoids, In: Ammonoid Paleobiology. 13. Springer. pp. 407-61. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-9153-2_12. ISBN 978-1-4757-9155-6. http://www.ammonit.ru/upload/arhiv/bucher-et-al-1996.pdf. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Yasunari Shigeta; Yuri D. Zakharov; Royal H. Mapes (28 September 2001). "Origin of the Ceratitida (Ammonoidea) inferred from the early internal shell features". Paleontological Research 5 (3): 201-13. http://www.kahaku.go.jp/english/research/researcher/papers/117527.pdf. Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Michael R. House (1994). "An Eocanites Fauna from the Early Carboniferous of Chile and its Palaeogeographic Implications". Annales de la Société géologique de Belgique 117 (1): 95-105. http://popups.ulg.ac.be/0037-9395/index.php?id=1990&file=1&pid=1988. Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Rafi Letzter (22 July 2019). "This Bloated 'Piglet Squid' Is Way Cuter Than a Real Piglet". Live Science. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ↑ Samantha Wishnak (22 July 2019). "This Bloated 'Piglet Squid' Is Way Cuter Than a Real Piglet". Live Science. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Joe Shimmin (2008). An Introduction to Belemnites. United Kingdom: UKFossils. http://www.ukfossils.co.uk/guides/belemnites.htm. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ↑ J. Kullman; D. Korn; M. S. Petersen (2000). Pendleian (Late Mississippian) Cephalopods. Tubingen: GONIAT Database System, version 2.90. http://www.ammonoid.com/pendleian.htm. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Larisa A. Doguzhaeva; Royal H. Mapes; Harry Mutvei (February 2002). "Shell Morphology and Ultrastructure of the Early Carboniferous Coleoid Hematites FLOWER & GORDON, 1959 (Hematitida ord. nov.) from Midcontinent (USA)". Abhandlungen der Geologischen Bundesanstalt-A. 57: 299-320. http://www.landesmuseum.at/pdf_frei_remote/AbhGeolBA_57_0299-0320.pdf. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ↑ Charles William (2009). Belemnites. Different Directions. http://go2add.com/paleo/belemnites.php. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Liza Carruthers (16 April 2015). nautilus. The Worlds of David Darling. http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/N/nautilus.html. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 Andrew S. Gale; William James Kennedy; David Martill (January 2017). "Mosasauroid predation on an ammonite – Pseudaspidoceras – from the Early Turonian of south-eastern Morocco". Acta Geologica Polonica 67 (1): 31-46. doi:10.1515/agp-2017-0003. https://geojournals.pgi.gov.pl/agp/article/download/25689/pdf. Retrieved 2017-05-26. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Gale" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ International Commission on Stratigraphy 2017

- ↑ Dmitry A. Ruban (2009). "The survival of megafauna after the end-Pleistocene impact: a lesson from the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary". Geologos 15 (2): 129–32. https://repozytorium.amu.edu.pl/bitstream/10593/166/1/Geologos_15_2_Ruban.pdf. Retrieved 2016-10-25.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Marcin Machalski (2005). "Late Maastrichtian and earliest Danian scaphitid ammonites from central Europe: Taxonomy, evolution, and extinction". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 50 (4): 653–96. http://yadda.icm.edu.pl/yadda/element/bwmeta1.element.agro-article-e9991b4c-1191-4b3c-b89f-71fb4cd6cac7/c/app50-653.pdf. Retrieved 2016-10-25.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Felix M. Gradstein; Frits P. Agterberg; James G. Ogg; Jan Hardenbol; Paul Van Veen; Jacques Thierry; Zehui Huang (1995). A Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Time Scale, In: Geochronology Time Scales and Global Stratigraphic Correlation. SEPM Special Publication No. 54. Society for Sedimentary Geology. doi:1-56576-024-7. http://archives.datapages.com/data/sepm_sp/SP54/A_Triassic_Jurassic_and_Cretaceous_Time_Scale.htm. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- ↑ Gaidheal1 (May 16, 2012). "Cretaceous Period". Retrieved 2012-07-24.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 JM Watson (28 July 1997). Index Fossils. Reston, Virginia USA: US Geological Survey. http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/geotime/fossils.html. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ↑ Mesozoic Cephalopods

- ↑ Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life (12 August 2021). "Baculites Species present in the Cretaceous of the Western Interior Seaway". Bethsda, Maryland USA: Digital Atlas of Ancient Life, National Science Foundation. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ↑ Steve Diem and J. David Archibald (2005). "RANGE EXTENSION OF SOUTHERN CHASMOSAURINE CERATOPSIAN DINOSAURS INTO NORTHWESTERN COLORADO". Journal of Paleontology 79 (2): 251-258. doi:10.1.1.538.7263. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.538.7263&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 James E. Fassett and Maureen B. Steiner (1997). Anderson, O.; Kues, B.; Lucas, S. ed. Precise age of C33N-C32R magnetic-polarity reversal, San Juan Basin, New Mexico and Colorado, In: Mesozoic Geology and Paleontology of the Four Corners Area. New Mexico Geological Society. pp. 239-247. https://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/downloads/48/48_p0239_p0247.pdf. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ↑ Michael H. Hofmann, Anton Wroblewski and Ron Boyd (25 May 2011). "Mechanisms controlling the clustering of fluvial channels and the compensational stacking of cluster belts". Journal of Sedimentary Research 81: 670–685. doi:10.2110/jsr.2011.54. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/31904032/Hofmann_et_al.__2011.pdf?1379415492=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DHofmann_et_al_2011.pdf&Expires=1628787286&Signature=Odam60S2y-CjtZOWzgHfaC0xiK3FzD10tioqyQFilwYp2ncPL5uilc87PWvu1C1PEuCMgNvXIti7e~jpRUYAdM0ZNZ16C3wdMKYKWT5ZXtv8c0yeJOE4k1KxLIW5nL00975EpHWh3GMA02EfURyFQmItXBdftJmx74hx~v~J6E4jf7L5t8Zvqz60x-P4jww85rYSMwZxQQ0G2pUT8ALnJooN9ZaBYI33iXdZVPP9a-zhvED1zwINtddfW7FIlauUiLmfIqxCubalww6V9g8YgvuLgV5YAO~NSAt6JjVVcSYxuI~wMEf8eIaPmBDJi7VTZzJl3bDCjbF0mWDFB0omdA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ↑ Mychaluk, K.A.; Levinson, A.A.; Hall, R.H.. "Ammolite: Iridescent fossil ammonite from southern Alberta, Canada.". Gems & Gemology 37 (1): 4-25. http://freeshipping.www.canadianammolite.com/SP01.pdf#page=5. Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- ↑ R. A. Reyment (Colonial Geology and Mineral Resources). New Turonian (Cretaceous) ammonite genera from Nigeria. 4. pp. 149-164. http://fossilworks.org/bridge.pl?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=14614. Retrieved 2018-5-19.

- ↑ Paleobiology Database

- ↑ Encyclopedia of life

- ↑ Cretaceous Atlas of Ancient Life (2006). "Acanthoceras amphibolum". Bethesda, Maryland USA: Digital Atlas of Ancient Life, National Science Foundation. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ↑ Ammonites

- ↑ Claire E. L. Still The effects of sexual dimorphism on survivorship in fossil ammonoids: A role for sexual selection in extinction

- ↑ GBIF

- ↑ Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera (Cephalopoda entry)". Bulletins of American Paleontology 364: 560. http://strata.geology.wisc.edu/jack/showgenera.php?taxon=231&rank=class. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ↑ William A.Cobban, Ireneusz Walaszczyk, John D. Obradovich, and Kevin C. McKinney (2006). Mark D. Myers. ed. A USGS Zonal Table for the Upper Cretaceous Middle Cenomanian−Maastrichtian of the Western Interior of the United States Based on Ammonites, Inoceramids, and Radiometric Ages. Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 47. https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2006/1250/pdf/OF06-1250_508.pdf. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ↑ Puzosia at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 46.5 Sepkoski, Jack Sepkoski's Online Genus Database – Cephalopoda

- ↑ Amédro, F., Matrion, B., Magniez-Jannin, F., & Touch, R. (2014). La limite Albien inférieur-Albien moyen dans l’Albien type de l’Aube (France): ammonites, foraminifères, séquences. Revue de Paléobiologie, 33(1), 159-279.

- ↑ Wright, C. W. (1996). Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part L, Mollusca 4: Cretaceous Ammonoidea (with contributions by JH Calloman (sic) and MK Howarth). Geological Survey of America and University of Kansas, Boulder, Colorado, and Lawrence, Kansas, 362.

- ↑ "Paleobiology Database - Pectinatites". Retrieved 2014-05-28.

- ↑ Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part L (Ammonoidea). R.C. Moore (ed). Geological Soc of America and Univ. Kansas Press (1957), p L394

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Arkell, W.J.; Kummel, B.; Wright, C.W. (1957). Mesozoic Ammonoidea. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part L, Mollusca 4. Lawrence, Kansas: Geological Society of America and University of Kansas Press.

- ↑ Ryszard Marcinowski and Jost Wiedmann. The Albian Ammonites of Poland. Palaeontologia Polonica no. 50, 1990.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Bo Wang (May 13, 2019). "This ancient sea creature fossilized in tree resin. How'd that happen?". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ↑ Jann Vendetti (May 13, 2019). "This ancient sea creature fossilized in tree resin. How'd that happen?". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ↑ David Dilcher (May 13, 2019). "This ancient sea creature fossilized in tree resin. How'd that happen?". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ↑ Jocelyn Sessa (May 13, 2019). "This ancient sea creature fossilized in tree resin. How'd that happen?". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ↑ Christian Meister, Martin Aberhan, Joachim Blau, Jean-Louis Dommergues, Susanne Feist-Burkhardt, Ernie A. Hailwood, Malcom Hart, Stephen P. Hesselbo, Mark W. Hounslow, Mark Hylton, Nicol Morton1, Kevin Page, and Greg D. Price (1 June 2006). "The Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the base of the Pliensbachian Stage (Lower Jurassic), Wine Haven, Yorkshire, UK". Episodes 29 (2): 93-106. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2006/v29i2/003. https://www.episodes.org/journal/view.html?doi=10.18814/epiiugs/2006/v29i2/003. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ↑ J. Auajjara and J. Boulègue (1 October 2001). "Dolomitization patterns of the Liassic platform of the Tazekka Pb–Zn district, Taza, eastern Morocco: petrographic and geochemical study". Journal of South American Earth Sciences 16: 167-188. doi:10.1016/S0895-9811(03)00051-8. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jamal-Auajjar/publication/232723742_Auajjar_Boulegues_JSAES_2003/data/0912f509022d64b335000000/Auajjar-Boulegues-JSAES-2003.pdf. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Yuri D. Zakharov; Alexander M. Popov; Galina I. Buryi (April 2005). "Triassic Ammonoid Succession in South Primorye: 4. Late Olenekian – Early Anisian zones of the Atlasov Cape Section". Albertiana 32: 36-9. http://paleo.cortland.edu/Albertiana/issues/Albertiana_32.pdf#page=21. Retrieved 2015-01-24.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Heinz W. Kozur; Gerhard H. Bachmann (April 2005). "Correlation of the Germanic Triassic with the international scale". Albertiana 32 (4): 21-35. http://paleo.cortland.edu/Albertiana/issues/Albertiana_32.pdf#page=21. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- ↑ Aphantites, Surenitinae

- ↑ Genus Aphantites

- ↑ Ruzhencev & Bogoslovskaya 1978 Namyurskiy etap v evolyutsii ammonodey. Pozdnenamyurskiye ammonoidei. Trudy Paleontologicheskogo Instituta Akademiya Nauk SSSR, 167: 1-336, fig.1-108, pl.1-44; Moskva.

- ↑ David M. Work; Charles E. Mason (November 2004). "Mississippian (Late Osagean) Ammonoids from the New Providence Shale Member of the Borden Formation, North-Central Kentucky". Journal of Paleontology 78 (6): 1128-37. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<1128:MLOAFT>2.0.CO;2). http://www.psjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1666/0022-3360%282004%29078%3C1128%3AMLOAFT%3E2.0.CO%3B2. Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Eichenberg (1930). "Genus Mimagoniatites". GONIAT Online. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ↑ John Alroy (2014). "†Mimagoniatites Eichenberg 1930 (ammonite)". Australia: Macquarie University. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ↑ IONHexamoceras (15 April 2015). "Name - Hexamoceras". Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ↑ C. H. Holland (October 1987). "Aptychopsid Plates (Nautiloid Opercula) from the Irish Silurian". The Irish Naturalists' Journal 22 (8): 347-51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25539196. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Laura Geggel (30 March 2021). "500 million-year-old fossil is the granddaddy of all cephalopods". Live Science. https://www.livescience.com/ancient-octopus-relative-fossil.html. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Anne Hildenbrand (30 March 2021). "500 million-year-old fossil is the granddaddy of all cephalopods". Live Science. https://www.livescience.com/ancient-octopus-relative-fossil.html. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ↑ Anne Hildenbrand, Gregor Austermann, Dirk Fuchs, Peter Bengtson & Wolfgang Stinnesbeck (23 March 2021). "A potential cephalopod from the early Cambrian of eastern Newfoundland, Canada". Communications Biology 4: 388. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-01885-w. https://www.livescience.com/ancient-octopus-relative-fossil.html. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ↑ Martin R. Smith; Jean-Bernard Caron (December 2011). "Nectocaris and early cephalopod evolution reply to Mazurek & Zatoń". Lethaia Focus 44 (4): 369-72. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2011.00295.x. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1502-3931.2011.00295.x/full. Retrieved 2016-10-28.